The Renaissance in the Veneto and Friuli

[Burlington Magazine]

by Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo

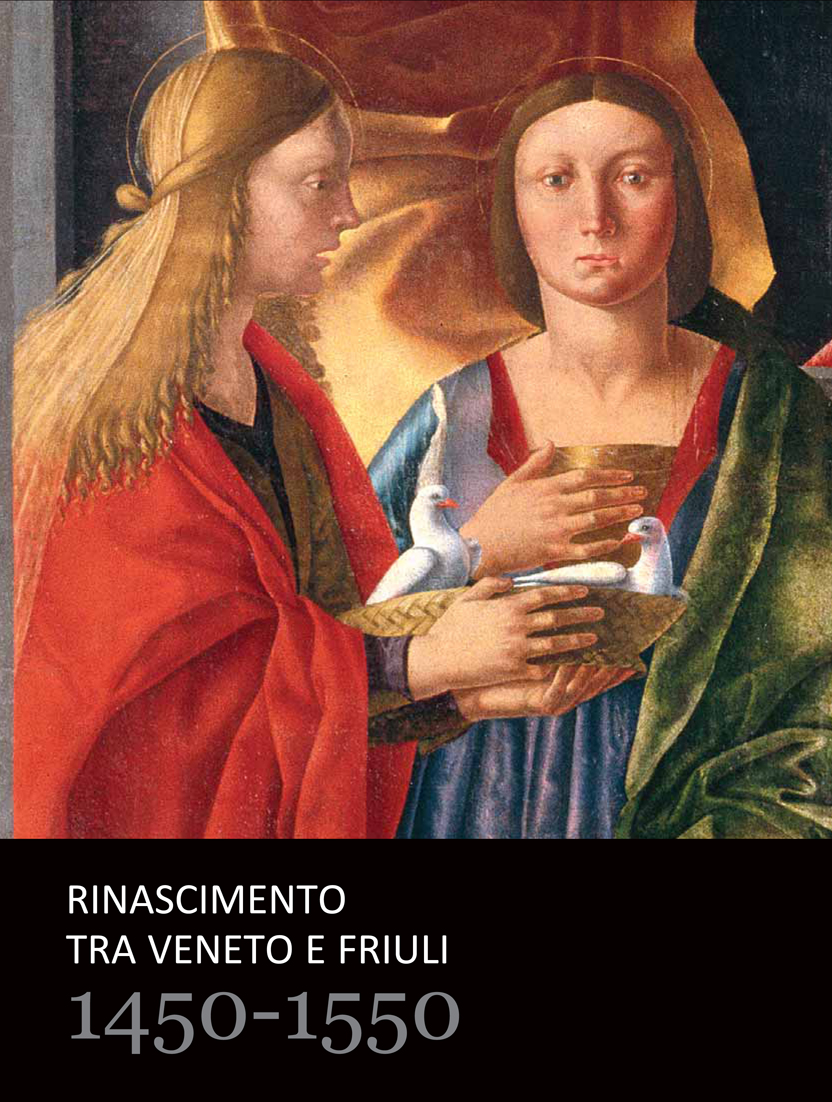

AS IS WELL known, the artistic and historical patrimony of Italy is managed by various regional Soprintendenze, always battling with insufficient funds to monitor the immense number of works, of many different types, in their care (paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, etc.), all of which have to be treated as an organic whole. A good example of a collaboration between various regional bodies is the exhibition Rinascimento tra Veneto e Friuli. 1450–1550, which was held at the Collegio Marconi, Portogruaro (closed 17th October), and was organised by the Soprintendenze per i Beni Artistici of Venice, Belluno, Padua and Treviso, on the borders of the Veneto and Friuli regions,1 a project that was first announced at a conference held at Portogruaro two years ago.2 In deference to the concept of territorial patrimony, not all the works discussed in the catalogue were present in the exhibition; about fifteen entries were for works that had to be visited on an itinerary, where the visitor could see them in their usual setting. Representing the Soprintendenze’s tutelage of many different art forms, the exhibition opened with a selection of manuscripts, seals, books, ceramics, goldsmiths’work and liturgical vestments, and focused on such artists as Andrea Bellunello, Domenico da Tolmezzo and Giovanni Martini da Udine, who were equally active as painters and sculptors. Such eclecticism is not surprising at this date (even in the major artistic centres almost all the large workshops received multimedia commissions), but in a peripheral region like this it explains the fundamentally artisanal nature of many of the works. In some cases, such as the fresco by Bellunello at Bagnara di Gruaro with its three carved Madonnas (cat. nos.23–26), the suspicion arises that the artist who signed the sculpture did not necessarily carve it. We still do not know much about the organisation of such workshops, but in some cases the interconnection between painting and sculpture is evident, as in Pietro da San Vito’s altarpiece at San Martino al Tagliamento (no.54) in which the architecture of the shrine that holds the polychromed statue of the Madonna is continued in the lateral painted wings (Fig.60).

In the context of such a retardataire cultural climate those artists who had contact with the protagonists of Venetian painting at the end of the quattrocento stood out: for instance, Gianfrancesco da Tolmezzo – whose relationship with Jacopo da Montagnana was particularly evident in his Pentecost in Pordenone Cathedral (no.39) and, above all, Giovanni Martini da Udine. His Virgin and Child with saints in the Correr Museum (1498; no.47) would suggest that he was trained in the Murano workshop of Alvise Vivarini, who also had equally close Battista da Udine (it would have been useful if some of his works had been included in the exhibition). While the Correr painting showed Giovanni Martini to have been a painter with the technical and compositional standards of a Jacopo da Valenza, even if intrinsically working in Alvise’s style, he was soon open to other influences, not exclusively of a pictorial nature. Starting with the St Mark enthroned with various saints (1501) in Udine Cathedral, his use of space would suggest that he studied architecture, and the solid and strongly foreshortened construction of the figures suggest he was already equally active as a sculptor. The same lucid style marks the Presentation of Jesus in the temple from Spilimbergo (1503; no.48). It was a pity that his next dated commission, St Ursula among the virgins of 1507, the main canvas of which is in the Brera, was represented only by its lunette of St Dominic and angels (Musei Civici, Udine; no.49), which poses a problem: the strongly Cimaesque character of the four music-making angels around the saint are attributed by many scholars with good reason to Girolamo di Bernardino da Udine, given their similarity to that painter’s only certain work, the signed Coronation of the Virgin (Musei Civici, Udine; not exhibited).

This would lead us to believe that this littleknown but not untalented petit-maître was associated with Martini in this commission, in which the influence of Carpaccio is equally evident in the Brera canvas.3 How did these artists acquire this style? It was not enough for Cima to have sent paintings to the region of Portogruaro – the Navolè polyptych (represented by the panel of St John the Baptist; no.42) and the famous Incredulity of St Thomas (National Gallery, London), which was not present but has a catalogue entry with a photograph taken by Carlo Naya (a photographer working in Venice at the end of the nineteeth century) when it was first sold in 1870 (nos.42–44) – and of Carpaccio, with the Redeemer with the instruments of the passion (1496; Musei Civici, Udine; not exhibited).

Giovanni Martini’s artistic development reached a stunning climax in Portogruaro Cathedral’s Presentation of Jesus in the temple (no.50; Fig.61), which was beautifully restored in 2008, while Francesca Borgo’s archival research allows us to date it to 1512–13.4

Although a certain hardness and stiffness mars both his minor works and his sculpture, it must be admitted that this large altarpiece is striking for its monumentality, for its dazzling tactile evocation of materials (marble, cloth) as well as the emotional intensity of his interpretation of the subject. It seems that we should now re-examine the authorship of the Redeemer blessing (Galleria Nazionale, Parma; Fig.62; not exhibited), attributed by Roberto Longhi to Pier Maria Pennacchi of Treviso, an attribution subsequently confirmed by most critics.5 Comparing this figure to those in the foreground of the Presentation one finds the same scrolled drapery, the solid, gnarled hands and feet, the rather stiff rendering of the heads, but also the splendid quality of light that creates depth that is typical of Giovanni Martini, represented in the exhibition by the earlier Redeemer from Udine (no.46).

The catalogue is well printed with good photographs and entries that are on the whole accurate, but the attribution to an anonymous Venetian artist of the fragmentary Virgin and Child and saints (no.53) from the church of S. Agnese e S. Lucia in Portogruaro is surprising given that it is certainly the work of the so-called Master of the Libreria Sacramoso at Verona, who very plausibly can be identified with the mature phase of Domenico Morone.6

1 Catalogue: Rinascimento tra Veneto e Friuli. 1450–1550. Edited by Anna Maria Spiazzi and Luca Majoli, with contributions by Caterina Furlan, Vincenzo Gobbo et al. 192 pp. incl. 101 col. + 2 b. & w. ills. (Comune di Portogruaro and Terra Ferma Edizioni, Crocetta del Montello), €25. ISBN 978–88–6322–048–3.

2 A.M. Spiazzi and L. Majoli, eds.: Tra Livenza e Tagliamento. Arte e cultura a Portogruaro e nel territorio concordiense tra XV e XVI secolo. Atti della giornata di studio, 28 novembre 2008, Portogruaro and Vicenza 2009.

3 This is not accepted by G. Bergamini: Giovanni Martini da Udine intagliatore e pittore, Mortigliano 2010, p.90.

4 F. Borgo: ‘Rinascimento tra Veneto e Friuli’, in Spiazzi and Majoli, op. cit. (note 1), pp.139–40; and F. borgo: ‘Un sarto per Giovanni e un tintore per Cima. La presentazione del Martini tra San Francesco e Sant’Andrea’, in Spiazzi and Majoli, op. cit. (note 2), pp.223–43.

5 See the entry by L. Viola in L. Fornari Schianchi: Galleria Nazionale di Parma. Catalogo delle opere

dall’Antico al Cinquecento, Milan 1997, p.138.

6 C. Predosin in Spiazzi and Majoli, op. cit. (note 1), pp.148–49. On the Veronese master – one of whose works is found not far from Portogruaro (G. Ganzer, ed.: La raccolta Galvani. Il gusto e il collezionismo in Friuli, Pordenone 1994, fig.2) – see L. Bellosi: ‘Un’indagine su Domenico Morone (e su Francesco Benaglio)’, in P. Rosenberg, C. Scailliérez and D. Thiébaut, eds.: Hommage à Michel Laclotte: Etudes sur la peinture du Moyen Age et de la Renaissance, Paris 1994, pp.281–303; G. Peretti: ‘Domenico Morone in San Bernardino’, in S. Marinelli and P. Marini, eds.: exh. cat. Mantegna e le arti a Verona 1450–1500, Verona (Palazzo della Gran Guardia) 2006–07, pp.117–23; and M. Molteni, ed.: Storia, conservazione e tecniche nella Libreria Sagramoso a San Bernardino a Verona, Verona (forthcoming).